Below is my previous research experience.

In my research, I explore various eco-evolutionary mechanisms which drive species interactions, and especially novel interactions between native and invasive species. I’m using primarily arthropods and plant-insect study systems to investigate how the lack of co-evolutionary history affects species adaptations to novel hosts, enemies, food sources, etc. I’m particularly curious how species behavior, morphology, and physiology change in response to novel environments. I’ve been working on a variety of projects that involve field and greenhouse experiments, molecular biology techniques, light and scanning electron microscopy, as well as systematic reviews and meta-analyses of existing ecological data.

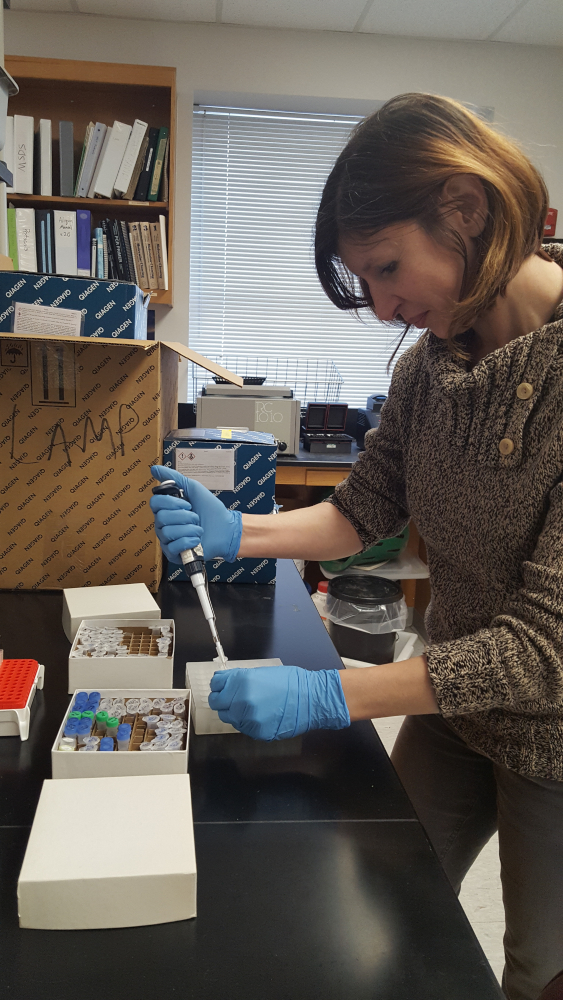

I’m currently an Assistant Research Scientist in Dr. Bill Lamp’s lab; I work on novel plant-insect interactions focusing on invasive species. I primarily use molecular gut content analysis which allows us to detect ingested plant DNA within insect gut contents,determine identity of ingested plant species, and create an accurate host plant range of an insect species. My work is heavily focused on the invasive spotted lanternfly, Lycorma delicatula: through using a single specimen DNA barcoding and meta-barcoding I decipher the lanternfly’s trophic interactions at each developmental stage. We hope that the results from this work will be invaluable for early detection and monitoring the nymphs and adults of Lycorma delicatula and predicting its novel host plants in the introduced range.

Below are my current and previous research projects which I conducted also as a postdoctoral researcher in Dr. Lamp’s lab; research associate at the University of Wisconsin-Madison; research assistant at the Unviersity of Cincinnati; and before that, as a researcher at the Institute of Cytology of the Russian Academy of Science and Herzen State University (St. Petersburg, Russia). My studies species have spanned various invertebrates (insects, isopods, snails, trematodes), as well as plants.

Spotted lanternfly (SLF), Lycorma delicatula (Hemiptera: Fulgoridae), is one of the most aggressive, highly invasive leafhopping pests in Mid-Atlantic region: it is extremely polyphagous and can utilize over 70 host plants, such as apple, plum, cherry, peach, apricot, grape, pine, tree of heaven, as well as many ornamental plants. Since its first detection in Berks County, PA in 2014, the spotted lantenrfly has rapidly spread to nearby states. What drives this invasion? How does the spotted lanternfly select its host plants? And how does the host plant range of this pest change? These are the questions I address in my research.

This is a multi-year research project which I started during my postdoctoral work in Dr. Bill Lamp’s lab. In this project, I’ve been focusing on SLF biology and ecology in relation to its host plant usage in the introduced range. Using a combination of field observations, microscopy, molecular biology tools, as well as analysis of existing ecological datasets I explore: (1) utilization of host plants at each developmental stage, (2) developmental changes in external morphology of the spotted lanternfly mouthparts and tarsi, (3) plant traits of SLF native and introduced host plants, to predict potential host plant expansion.

To confirm host plant consumption and explore the potential host plant range of the lanternfly, I’ve been using molecular biology techniques to detect host plant DNA within the lanternfly gut contents. I utilized Sanger sequencing to obtain a portion of plant chloroplast DNA region within the lanternfly gut contents. I successfully isolated and identified plant DNA for ‘single-DNA’-samples (i.e. when there is only one ingested host plant species in the lanternfly gut). I’m also using DNA meta-barcoding (using a NGS technology) to explore mixed DNA samples and determine a host plant range of each developmental stage of the spotted lanternfly.

Our current findings of plant DNA detection from the gut contents of the lanternfly nymphs (Avanesyan and Lamp 2020) suggest that while the observed lanternfly nymphs actively move on a host plant they may not utilize it for feeding. A substantial number of the nymphs (~90%) we have analyzed (collected during summer 2018) showed the ingested DNA from a host plant other than the plant from which the nymphs were collected. To reconstruct a list of all possible host plant species of the lanternfly we are starting conducting meta-barcoding of the lanternfly gut contents using a NGS approach (‘Amplicon-EZ’).

04/01/20: Our paper on molecular gut content analysis of the invasive spotted lanternfly, Lycorma delicatula, was published today in Insects special issue “Molecular Gut Content Analysis: Deciphering Trophic Interactions of Insects”! So exciting!

01/03/20: our MAES grant proposal on using a NGS-approach for meta-barcoding the lanternfly gut contents has just been funded!

10/01/19: I’m a Guest Editor for journal Insects, Special Issue “Molecular Gut Content Analysis: Deciphering Trophic Interactions of Insects”

11/15/18: presented! Here is my presentation.

07/07/18: we are making some good progress, and we’ve submitted an abstract for our oral presentation (A.Avanesyan and W. O. Lamp, “Use of molecular markers for plant DNA to determine host plant usage for potato leafhopper, Empoasca fabae”) to the ESA meeting in Vancouver, BC, Canada.

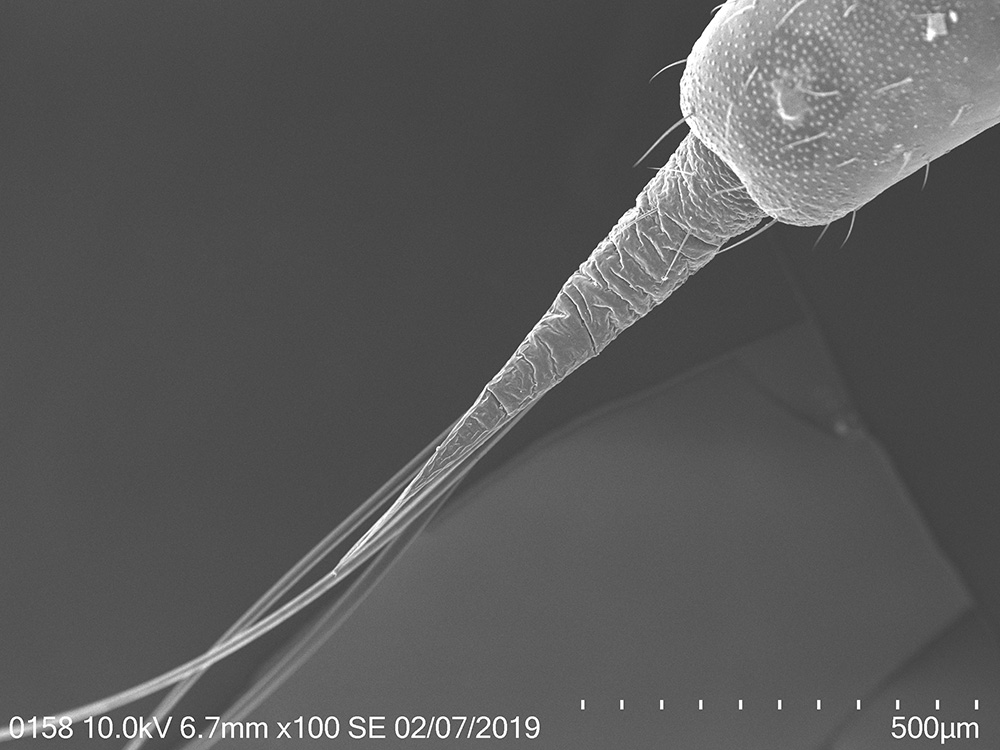

To explore the morphological adaptations of the lanternfly to host plant utilization, I focused on the following two objectives: (a) to assess changes in morphology of the lanternfly mouthparts (stylets and labium), and (b) to assess changes in morphology of the lanternfly tarsal tips (arolia and tarsal claws) at each developmental stage. The labium, stylets, and tarsal tips are the structures which are associated with primary contact of the lanternfly with its host plant, and which potentially facilitate the lanternfly successful host plant use. I assessed the developmental changes in these structures using both scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and morphometric analysis. As we expected, these structure undergo substantial morphological and morphometric changes throughout the lanternfly development which could potentially indicates the lanternfly association with certain host trees at each developmental stage.

The spotted lanternfly, Lycorma delicatula, on a host tree: 4th nymphal instar, 7/17/2018, Berks County, PA

12/27/19: Our paper “External morphology and developmental changes of tarsal tips and mouthparts of the invasive spotted lanternfly, Lycorma delicatula” has been just published in PLOS ONE! Here is our paper.

11/18/19: I’ve presented our updated results on the lanternfly external morphology at the Entomological Society of America Annual Meeting, Eastern Branch, March 9-11,2019. Blacksburg, VA. Here is my poster.

02/28/19: I’ve finished the 2nd round of scanning electron microscopy of the lanternfly mouthparts and tarsi. Most of the beautiful SEM images are included in my poster for the upcoming EB-ESA meeting.

02/23/19: I’ve presented at the Annual Meeting of the Maryland Organic Food & Farming Association (Maryland Dept. of Agriculture, Annapolis, MD). My talk was on the lanternfly biology, behavior, and host plant usage.

Avanesyan, A., Maugel T.K., and W. Lamp (2019) External morphology and developmental changes of tarsal tips and mouthparts of the invasive spotted lanternfly, Lycorma delicatula. PLOS ONE, doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226995 file_downloadfull text

Avanesyan, A., Maugel, T., and W. Lamp. (2019) External morphology and developmental changes of tarsal tips and mouthparts of the invasive spotted lanternfly, Lycorma delicatula. Annual Meeting of the Entomological Society of America, St. Lois, MO. Poster presentation file_downloadfull text

Avanesyan, A. (2019) Spotted lanternfly: information and update. Maryland Organic Food & Farming Association, Maryland Dept. of Agriculture, Annapolis, MD. Invited talk file_downloadfull text

Below are various DNA barcoding projects I’ve been involved in Dr. Bill Lamps’ lab. Some of these projects were conducted with great help from my mentees.

12/01/21: My mentee, Anya, has submitted an abstract for her poster presentation “Using molecular gut content analysis to characterize PLH (Empoasca fabae) movement within a farmscape” for the upcoming meeting of the Entomological Society of America, Eastern Branch (in Philadelphia, PA)

10/10/21: I continue working on molecular gut content analysis of the potato leafhopper. Together with my new mentee, Anya, we’ve started applying a meta-barcoding approach to the bulk samples of the potato leafhopper, to identify all the ingested plants.

11/04/20: Our paper on detecting ingested host plant DNA in potato leafhopper was published online today in Journal of Economic Entomology! So exciting!

11/15/18: presented! Here is my presentation.

07/07/18: we are making some good progress, and we’ve submitted an abstract for our oral presentation (A.Avanesyan and W. O. Lamp, “Use of molecular markers for plant DNA to determine host plant usage for potato leafhopper, Empoasca fabae”) to the ESA meeting in Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Avanesyan, A., Illahi, N., and W.O. Lamp. (2021) Detecting ingested host plant DNA in potato leafhopper, Empoasca fabae: potential use of molecular markers for gut content analysis. Journal of Economic Entomology, 114(1), 2021, 472–475. file_downloadfull text

Avanesyan, A., and W. Lamp (2018) Use of molecular markers for plant DNA to determine host plant usage for potato leafhopper, Empoasca fabae. Annual Meeting of the Entomological Society of America: 2018 ESA, ESC, and ESBC Joint Annual Meeting, Vancouver, BC, Canada. Oral presentation. file_downloadfull text

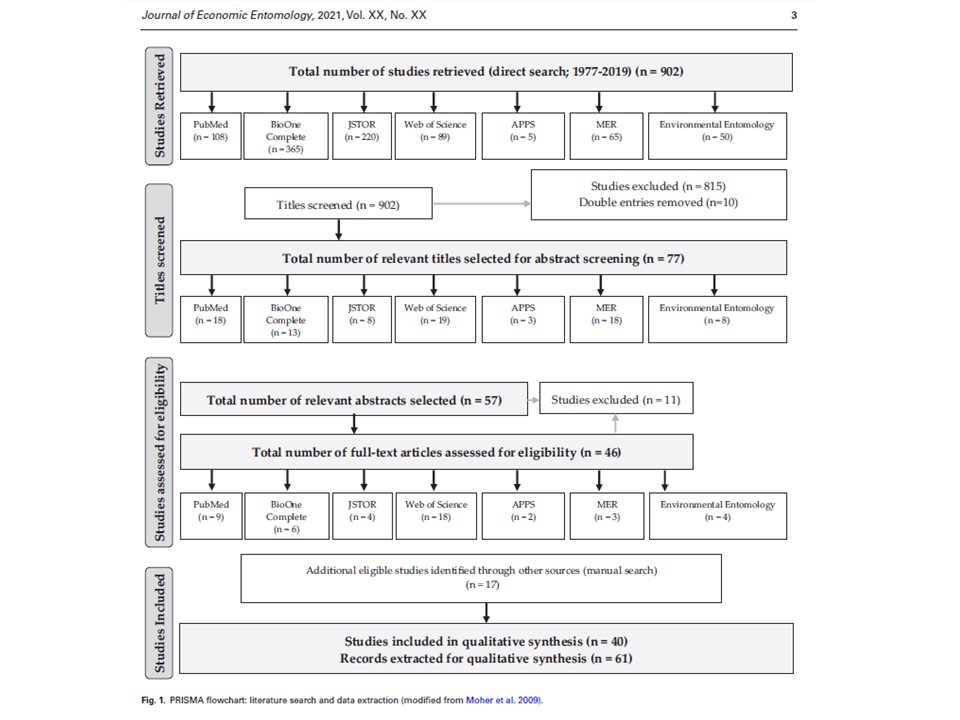

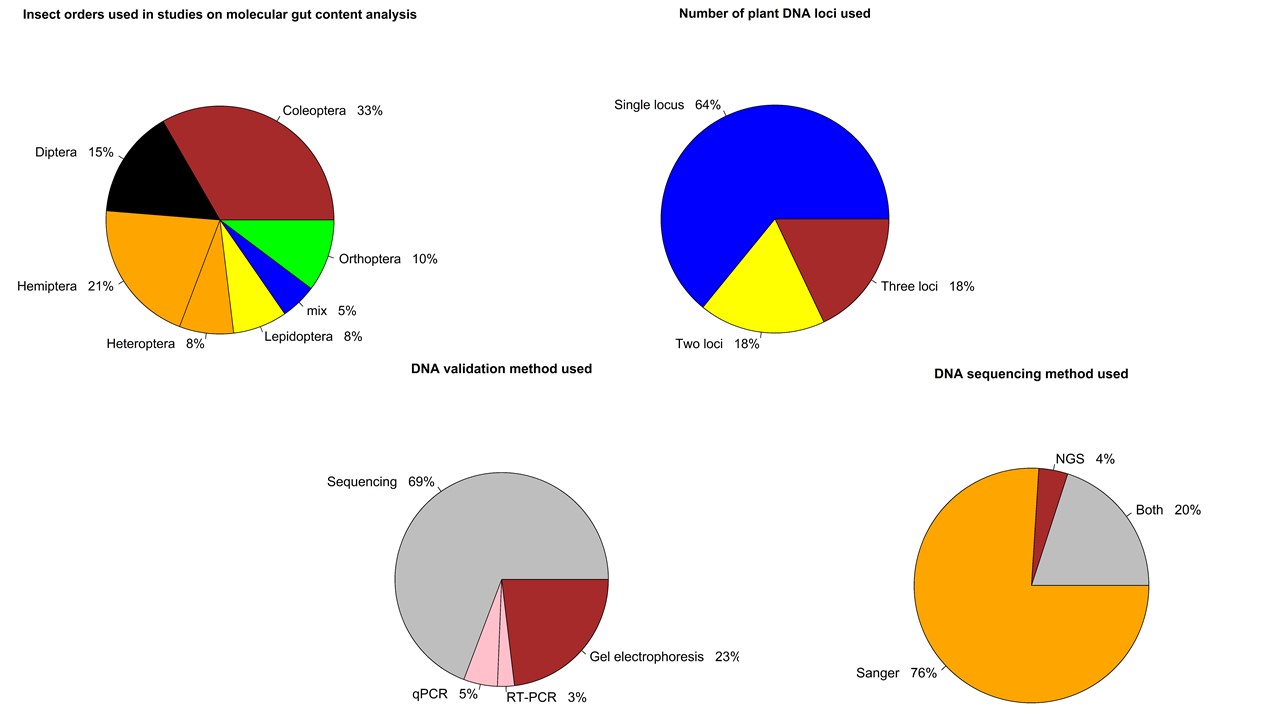

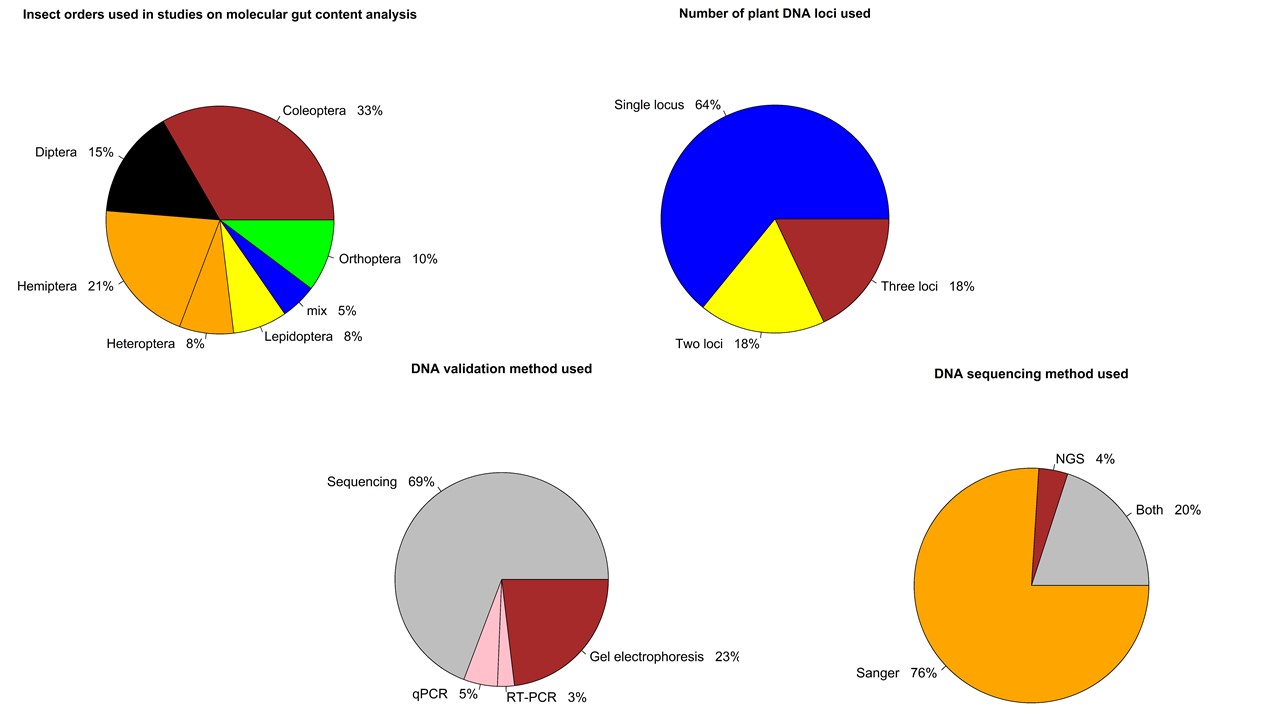

The idea for this project came from our DNA work with the lanternfly gut contents. I tried a few regions of the chloroplast DNA which were candidates for plant DNA detection within the lanternfly guts, and only one of them yielded good amplification and sequencing results. Unlike relatively straight forward DNA barcoding of ‘fresh’ plants the situation with ingested plants are more complex: the plant DNA is degraded, plant DNA concentration in insect guts is often extremely low (compared to that in the intact plants), and we often do not know the time of consumption before we extract the ingested plant DNA. Choosing and testing various loci are always time-consuming, and even though there are more and more studies being published on molecular gut content analysis, the information on how to choose the best targeted gene for detecting ingested plant DNA is very limited.

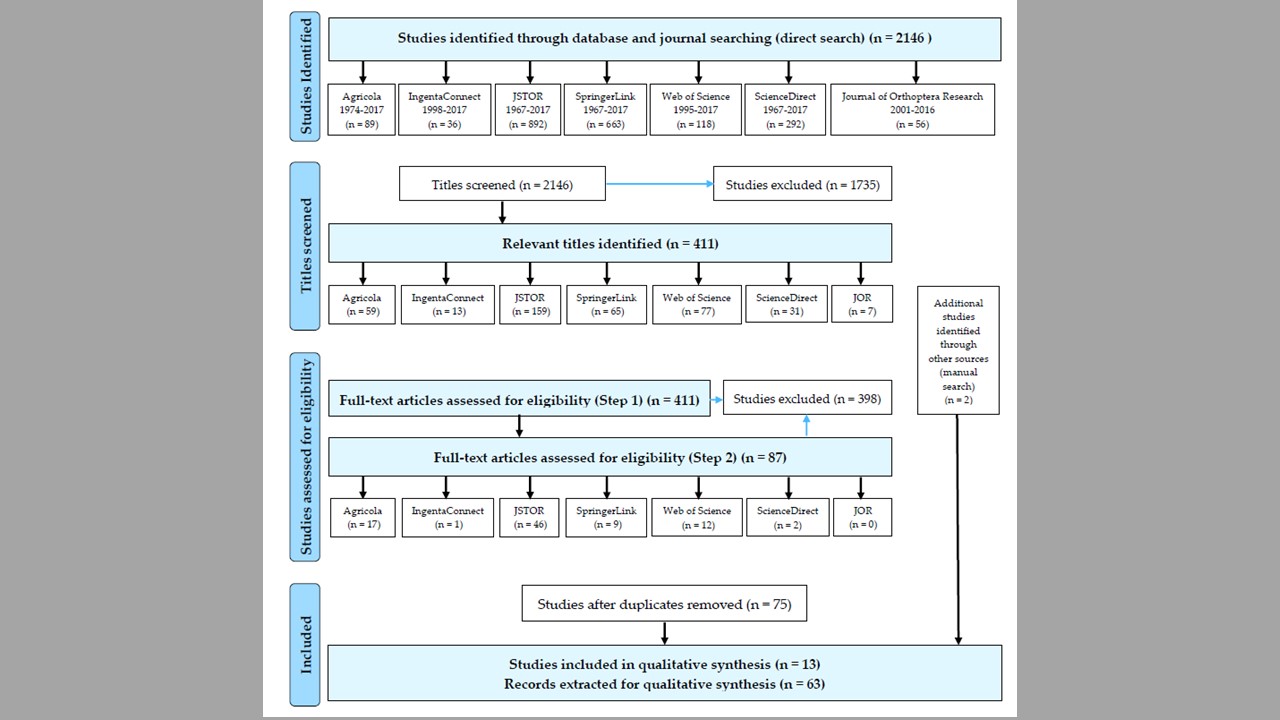

Together with Hannah, an undergraduate student, my great helper and mentee, we have retrieved 902 experimental studies on insect gut content analysis from 4 public databases and 3 research journals. We are currently screening these articles according our several inclusion criteria and selecting the ones we are going to proceed with to the data analysis. Ultimately, we are interested in the following two questions: (1) what regions of plant DNA are commonly used for insect molecular gut content analysis? (2) what validation methods do the researchers use to determine the success of detection of ingested plant DNA?

We hope that outcomes of our systematic review would help us provide the methodological guidelines for the researchers for choosing the targeted regions of plant DNA which can be reliably detected within insect gut contents.

03/21/21: It has been a long process, but we did it! Our review paper on choosing an effective PCR-based approach for diet analysis of insect herbivores is published in Journal of Economic Entomology! So exciting!

09/09/20: our manuscript, with my mentee, Hannah, as a co-author, is currently in revision.

02/05/20: secondary references are retrieved from the selected articles; we are currently extracting data from the studies.

11/20/19: 902 research articles on insect gut content analysis published between 1977-2019 were retrieved; 105 of relevant titles and 68 relevant abstracts were screened; of those, 55 articles were selected for full-text screening.

This project had developed from the results of my doctoral dissertation. In my doctoral research, I found feeding preferences of Melanoplus grasshoppers for introduced, sometimes invasive plants, and I was curious whether all the acridid grasshoppers demonstrate such feeding behavior in response to novel host plants. To address this question, I conducted a systematic review to identify patterns of feeding preferences of acridid grasshoppers for native versus introduced plants and, consequently, grasshopper potential for biotic resistance of native communities.

The analysis of 63 records of feeding preference trials for 28 North-American grasshopper species (retrieved from 2146 studies published during 1967–2017) has demonstrated a preference of grasshoppers for introduced host plants, and identified 12 preferred introduced plants with high or middle invasive ranks. A significant effect of the life stage (p < 0.001), but not the experimental environment, plant material, and measurements, on grasshopper preferences for introduced plants was also detected. Overall, results suggest a potential of acridid grasshoppers to contribute to the biotic resistance of native communities. The review also provides methodological recommendations for future experimental studies on grasshopper-host plant interactions.

10/07/18: the manuscript has been published in Plants! I was also featured in our departmental news.

07/07/18: I’ve submitted a poster presentation on this review to the upcoming ESA meeting in Vancouver, BC, Canada. I’m also going to present it here, at the University of Maryland research symposium organized by the Office of Postdoctoral Affairs.

05/18/18: the manuscript has been submitted!

Avanesyan, A. (2018) Should I eat or should I go? Acridid grasshoppers and their novel host plants: implications for biotic resistance. Plants: Special Issue “Plants Interacting with other Organisms: Insects”, 7(4), 83. Invited paper file_downloadfull text

Avanesyan, A. (2018) Should I eat or should I go? Acridid grasshoppers and their novel host plants: implications for biotic resistance. Annual Meeting of the Entomological Society of America: 2018 ESA, ESC, and ESBC Joint Annual Meeting, Vancouver, BC, Canada. Poster presentation file_downloadfull text

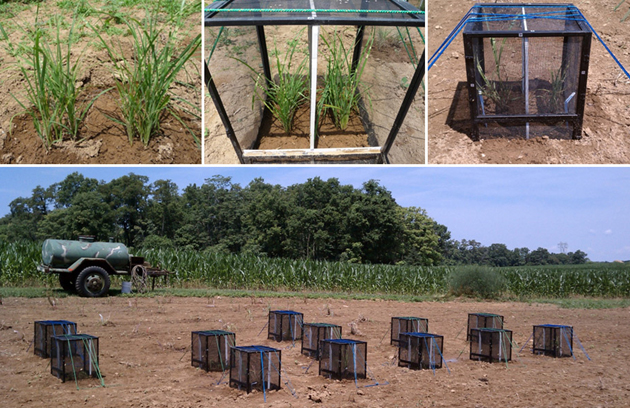

Introduced grasses can aggressively expand their range and invade native habitats. Miscanthus sinensis, the chinese silver grass, is an introduced ornamental grass with 100+ cultivars of various invasive potential. Although Miscanthus sinensis is a gorgeous ornamental plant and important biofuel source, it can be highly invasive in some states; however, not all of its cultivars are invasive. For this project, in 2018-2019, I conducted field and greenhouse experiments to explore plant resistance and tolerance to grasshopper herbivory in five cultivars of Miscanthus sinensis. The results of this project demonstrated that plant responses varied among the cultivars during a season; all the cultivars, but “Zebrinus”, demonstrated a significant increase in plant tolerance by the end of the growing season regardless of the amount of sustained leaf damage. Different patterns in plant responses from “solid green” and “striped/spotted” varieties were recorded, with the lowest plant resistance detected for “Autumn Anthem” in the cage experiment. Our results have important applications for monitoring low-risk invaders in protected areas, as well as for biotic resistance of native communities to invasive grasses.

12/25/2021: The manuscript has been published in Plants!

09/20/21: I was invited to submit our study on responses of Miscanthus sinensis cultivars to insect herbivory to Plants, Special Issue “Invasive Alien Species in Protected Areas”.

07/27/20: I presented this project at the Botany-2020 virtual meeting, Annual Meeting of the Botanical Society of America. Here is a video recording of my talk, and here are my slides.

09/20/19: I’ve finished the analysis of the data we collected in 2018 and 2019 summer seasons; we see some interesting patterns in plant tolerance to herbivory and their association with plant morphological appearance; and I’m about to start working on the manuscript.

Avanesyan, A., and W.O. Lamp. (2022) Response of five Miscanthus sinensis cultivars to grasshopper herbivory: implications for monitoring of invasive grasses in protected areas. Plants: Special Issue “Invasive Alien Species in Protected Areas “, 11(1), 53, https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11010053. Invited paper file_downloadfull text

Avanesyan, A., and W. Lamp. (2020) Variation in plant responses to grasshopper herbivory among the cultivars of the introduced Miscanthus sinensis. Botany 2020: Annual Meeting of the Botanical Society of America. Oral presentation file_downloadfull text

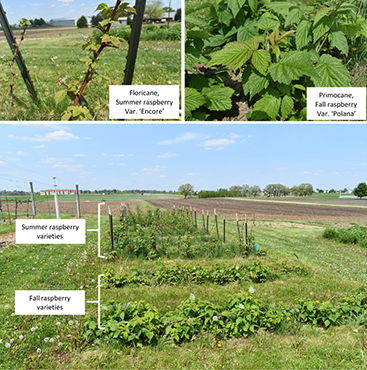

In my postdoctoral work at the University of Wisconsin-Madison I studied one of the emerging insect pests – the spotted wing drosophila, Drosophila suzukii Matsumura (Diptera: Drosophilidae). This is a highly invasive insect species, which attacks undamaged ripening fruit of a wide variety of soft-skinned fruits and berries. Native to Southeast Asia, currently it is observed in Europe, North America, and South America. Drosophila suzukii has demonstrated a very high dispersal capacity and remarkable phenotypic plasticity – during only a couple of decades since its first introduction in Hawaii, D. suzukii invaded different temperate regions and now is being monitored in many northern and eastern states, as well as Canada.

I worked on several projects on different aspects of D. suzukii biology and population distribution. I coordinated a multi-state bait comparison project for determining optimal attractants for D. suzukii. This project was conducted in Minnesota; we set up fly traps with eight different baits and conducted monitoring of D. suzukii in raspberry during several weeks. I also developed experimental design for the spatial and temporal distribution project which was supposed to be conducted later in the season when population of D. suzukii could be established.

I was also actively involved in a project on D. suzukii seasonal phenology focused on overwintering of D. suzukii and the effect of temperature and humidity on D. suzukii seasonal abundance. We are currently writing a paper on D. suzukii seasonal phenology which includes an analysis of the interactions between D. suzukii seasonal abundance and temperature and humidity dynamics during the collecting seasons in 2014-2015.

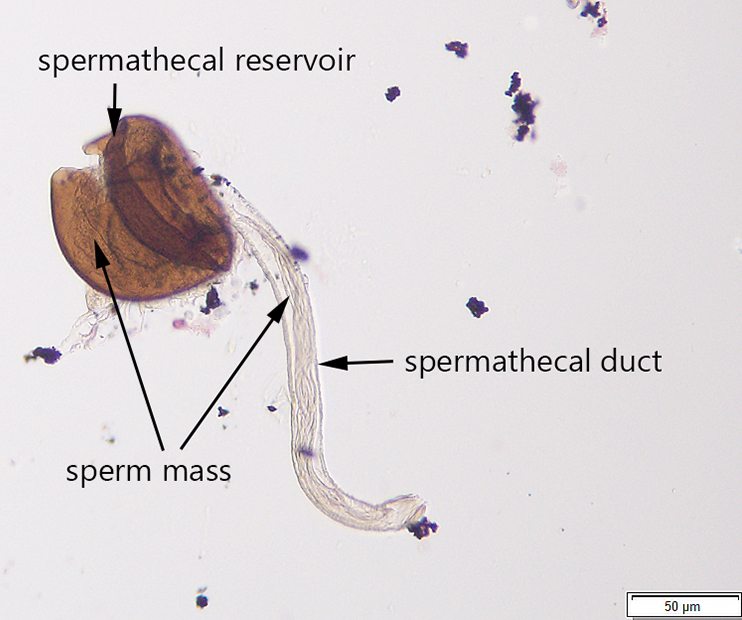

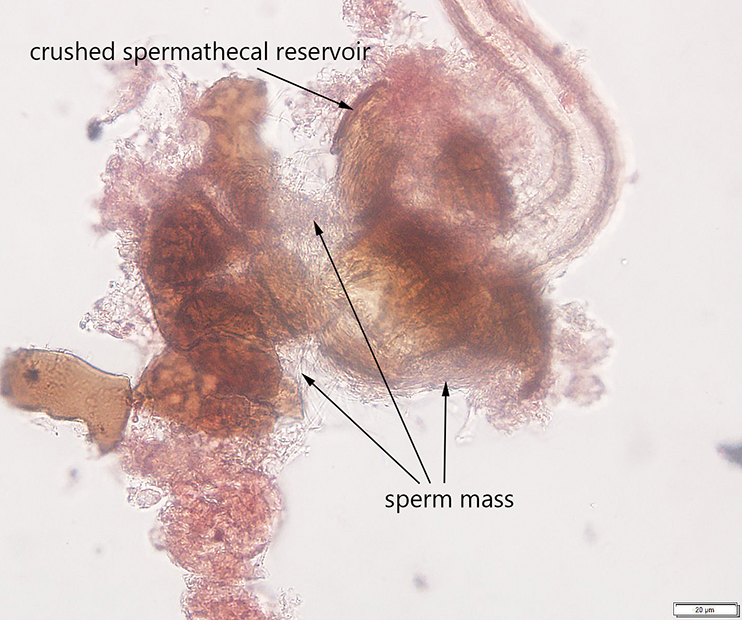

Additionally, I developed a protocol for tissue preparation, isolating spermathecae, and determining mating status of D. suzukii, which we have applied in our bait comparison and phenology studies. This protocol has been recently published in Insects (Special issue on invasive species). In this paper, we also demonstrated how this protocol can be applied for both field collected flies and flies reared in the lab, including fly specimens stored on a long-term basis.

Guédot, C., Avanesyan, A., and K. Hietala-Henschell. (2018) Effect of temperature and humidity on the seasonal phenology of Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in Wisconsin. Environmental Entomology 47(6): 1365–1375. file_downloadfull text

Jaffe, B.D., Avanesyan, A., Bal, H. K., Grant, J., Grieshop, M.J., Lee, J.C., Liburd, O.E., Rhodes, E., Rodriguez-Saona, C., Sial, A.A., Zhang, A., and C. Guédot (2018) Multistate comparison of attractants and the impact of fruit development stage on trapping Drosophila suzukii (Diptera: Drosophilidae) in raspberry and blueberry. Environmental Entomology, 47(4): 935–945. exit_to_applink to publication

Avanesyan, A., Jaffe, B.D., and C. Guédot (2017) Isolating spermatheca and determining mating status of the invasive spotted wing drosophila, Drosophila suzukii: a protocol for tissue dissection and its applications. Insects: Special issue “Invasive Insect Species”. 8(1), 32; doi:10.3390/insects8010032. Invited paper. file_downloadfull text

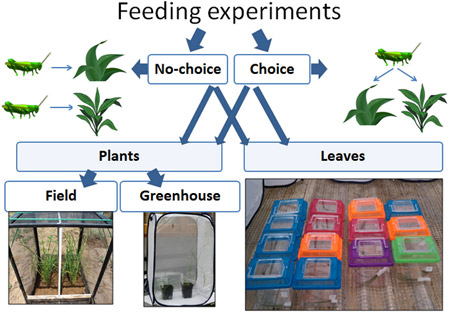

In my dissertation at the University of Cincinnati I explored the interactions between insect herbivores and their host plants within the context of invasion ecology. Specifically, I was interested in the potential impact of generalist insects on the successful spread of exotic plants. Using a grasses-grasshoppers model, I combined behavioral and molecular approaches to explore (1) tolerant and resistant responses of native and exotic grasses to herbivory by grasshoppers, and (2) grasshopper feeding preferences on these plants. I conducted laboratory and field experiments at two research centers (University of Cincinnati and University of Maryland) to explore whether plant responses to different insect populations were similar, and whether the insects acted in the same way.

Ph.D. Dissertation: Native versus exotic grasses: the interaction between generalist insect herbivores and their host plants. (Alina Avanesyan, 2014; University of Cincinnati)

Advisor: Dr. Theresa Culley, Professor, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Cincinnati

My study grasses species were: native Andropogon gerardii and Bouteloua curtipendula, and exotic, potentially invasive, Miscanthus sinensis and Bothriochloa ischaemum. I conducted choice (many grasses) and no-choice (one grass species) experiments; experiments in the field and in the greenhouse; experiment with intact plants and with their clipped. To estimate plant resistance and tolerance I measured the amount of leaf tissue consumed by grasshoppers, the growth of plants during the feeding and their re-growth after the feeding, the grasshopper’s growth on different plants and many other things. In the same behavioral experiments with plants and, additionally, in the experiments with clipped leaves, I estimated leaf consumption, the proportion of leaves consumed by grasshoppers, as well as their assimilation efficiency and relative consumption rate on native and exotic grasses. I was conducting most of my experiments in Ohio (UC Center for Field Studies and The Culley Laboratory), but also conducted some at the Western Maryland Research & Education Center – thanks to Dr. William Lamp who was a member of my dissertation committee and provided me with access to this wonderful research facility, and Tim Ellis, the Center’s Agronomy Program Manager, whose help with preparing the plot and growing plants was invaluable.

Also see: How to build a cage

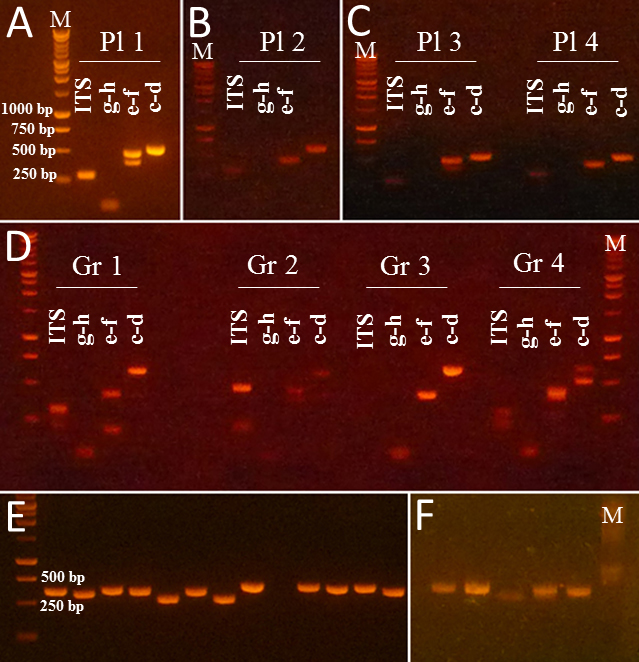

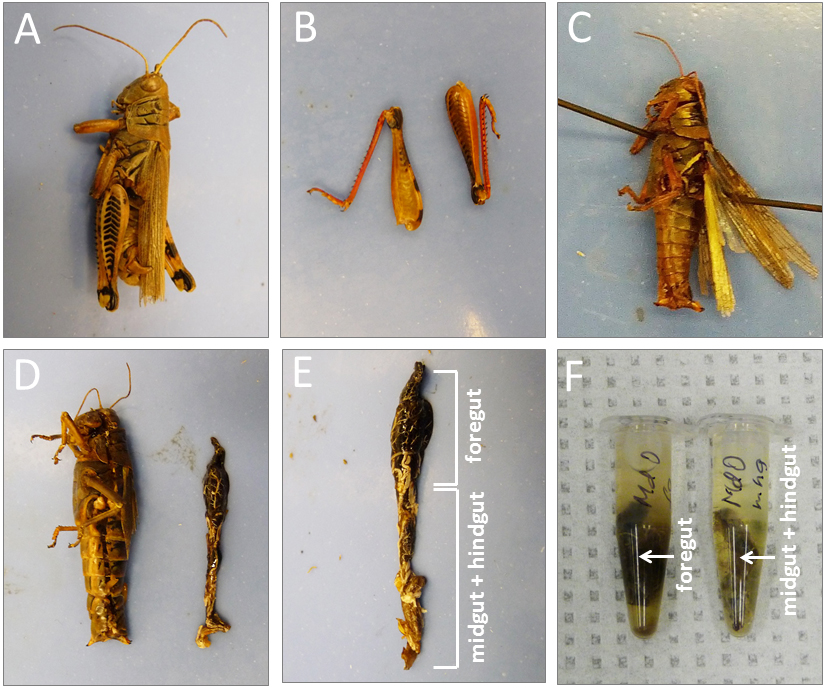

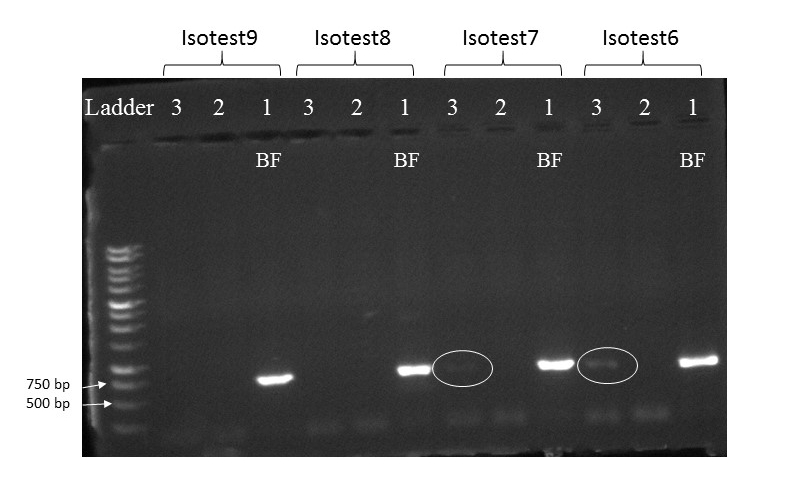

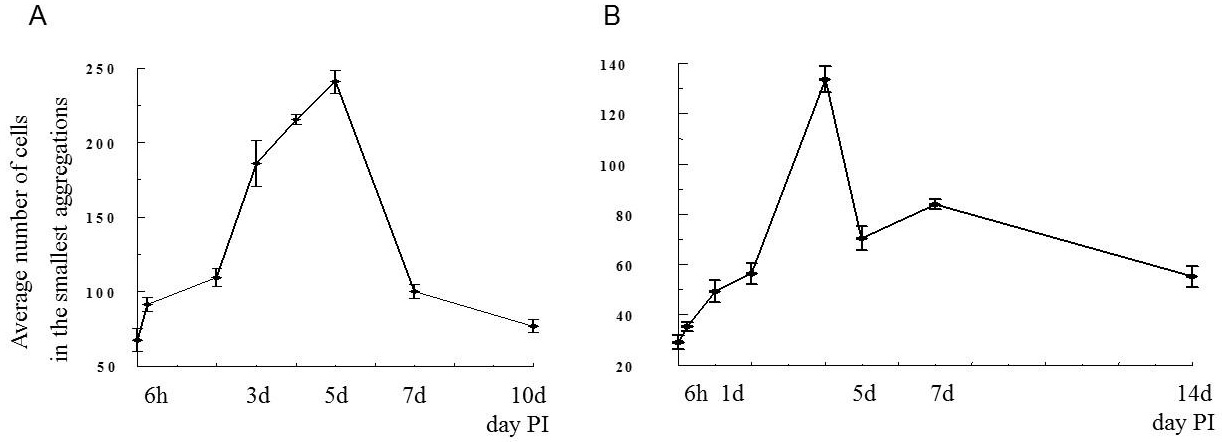

As part of my dissertation, I developed a new PCR-based method for accurate detection of plant meals from grasshopper guts, which had not been described in experimental studies. Using the developed protocol, I successfully amplified fragments (~500 bp) of the non-coding region of the chloroplast trnL (UAA) gene from grasshopper guts; the plant DNA was found to be detectable up to twelve hours post ingestion (PI) in nymphs and up to 22 h PI in adult grasshoppers. This method was published in Applications in Plant Sciences and was featured in Botanical Society of America News, ScienceDaily, ScienceNewsLine, Phys.org, LabRoots, EurekAlert!, as well as Down to Earth (a science magazine of The Society For Environmental Communications in India).

My results from both, behavioral experiments and molecular confirmation of diet, demonstrated that

exotic grasses have lower resistance (the ability to reduce damage) to grasshopper feeding than

native grasses; whereas plant tolerance (the ability to maintain fitness while sustaining damage) to

herbivory does not differ between native and exotic grasses. My results suggested that exotic

grasses that do not have a coevolutionary history with native grasshoppers are less adapted to

reduce damage from these herbivores, although they tolerate them similar to native plants. These

results contributed to our understanding of the trade-off between plant tolerance and plant

resistance to herbivory and the possible mechanisms of the success of exotic plans in the introduced

range – i.e., mechanisms that facilitate plant invasion. The important applications of this project

are: effective control of invasive plants, predictions of plant invasion, and ecological restoration

of native communities.

Avanesyan, A., and T.M. Culley (2016) Tolerance of native and exotic prairie grasses to herbivory by Melanoplus grasshoppers: application of a non-destructive method for estimating plant biomass changes as a response to herbivory. The Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 144(1):15-25. exit_to_applink to publication

Avanesyan, A., and T.M. Culley (2015) Feeding preferences of Melanoplus femurrubrum grasshoppers on native and exotic grasses: behavioral and molecular approaches. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 157: 153-163. exit_to_applink to publication

Avanesyan, A., and T.M. Culley (2015) Herbivory of native and exotic North-American prairie grasses by nymph Melanoplus grasshoppers. Plant Ecology 216: 451-464. file_downloadfull text

Avanesyan, A. (2014) Plant DNA detection from grasshopper gut contents: a step-by-step protocol, from tissues preparation to obtaining plant DNA sequences. Applications in Plant Sciences 2(2):1300082. file_downloadfull text

Below are various DNA barcoding projects I was involved at different times during my doctoral studies at the University of Cincinnati and postdoctoral work in Dr. Bill Lamps’ lab (at the University of Maryland). Some of these projects were conducted with great help from my mentees.

Avanesyan, A., Illahi, N., and W.O. Lamp. (2021) Detecting ingested host plant DNA in potato leafhopper, Empoasca fabae: potential use of molecular markers for gut content analysis. Journal of Economic Entomology, 114(1), 2021, 472–475. file_downloadfull text

Avanesyan, A., and W. Lamp (2018) Use of molecular markers for plant DNA to determine host plant usage for potato leafhopper, Empoasca fabae. Annual Meeting of the Entomological Society of America: 2018 ESA, ESC, and ESBC Joint Annual Meeting, Vancouver, BC, Canada. Oral presentation. file_downloadfull text

This was a new challenge in my DNA barcoding work. I amplified DNA from dragonfly prey items. In addition to a gut content analysis, I was working with degraded DNA from dragonfly feces. For this project, I successfully amplified and sequenced COI partial gene from dragonfly feces produced during the first 2 hours post ingestion. The sequence analysis with subsequent BLAST results showed that the prey item was a crane fly. Surprisingly enough the DNA from the crane fly wasn’t degraded and an isolated fragment of 667 bp showed good sequence quality. These exciting results can make identification of dragonfly prey possible and accurately confirm (or even point to new) trophic interactions in dragonfly natural habitats.

The idea for this project came from our DNA work with the lanternfly gut contents. I tried a few regions of the chloroplast DNA which were candidates for plant DNA detection within the lanternfly guts, and only one of them yielded good amplification and sequencing results. Unlike relatively straight forward DNA barcoding of ‘fresh’ plants the situation with ingested plants are more complex: the plant DNA is degraded, plant DNA concentration in insect guts is often extremely low (compared to that in the intact plants), and we often do not know the time of consumption before we extract the ingested plant DNA. Choosing and testing various loci are always time-consuming, and even though there are more and more studies being published on molecular gut content analysis, the information on how to choose the best targeted gene for detecting ingested plant DNA is very limited.

Together with Hannah, an undergraduate student, my great helper and mentee, we have retrieved 902 experimental studies on insect gut content analysis from 4 public databases and 3 research journals. We are currently screening these articles according our several inclusion criteria and selecting the ones we are going to proceed with to the data analysis. Ultimately, we are interested in the following two questions: (1) what regions of plant DNA are commonly used for insect molecular gut content analysis? (2) what validation methods do the researchers use to determine the success of detection of ingested plant DNA?

We hope that outcomes of our systematic review would help us provide the methodological guidelines for the researchers for choosing the targeted regions of plant DNA which can be reliably detected within insect gut contents.

09/09/20: our manuscript is currently in revision.

02/05/20: secondary references are retrieved from the selected articles; we are currently extracting data from the studies.

11/20/19: 902 research articles on insect gut content analysis published between 1977-2019 were retrieved; 105 of relevant titles and 68 relevant abstracts were screened; of those, 55 articles were selected for full-text screening.

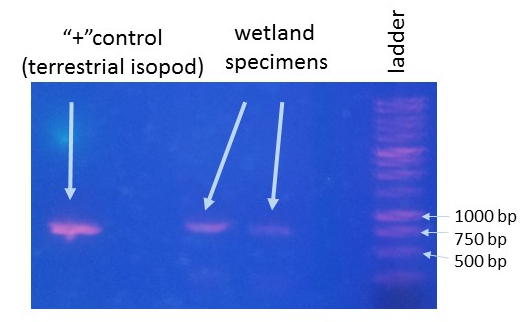

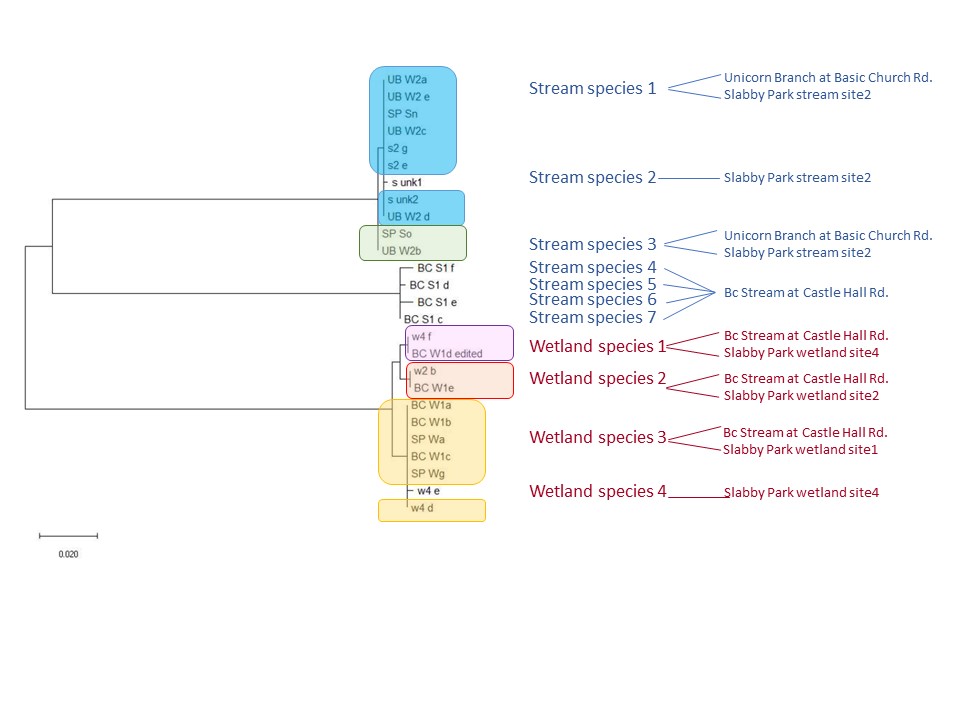

This is an ongoing project in Dr. Lamp’s lab. Using isopods from multiple wetland sites and streams in Maryland Delmarva Bays Wetlands we explore the potential connectivity between wetland and stream communities. Morphological identification of isopod species is tricky, and DNA barcoding, which I’m focusing on, is very helpful for estimating how ‘close’ wetland isopod species are to the isopod species inhabiting streams. I mentored three students in this DNA barcoding work, and together with my mentees we isolated and sequenced a portion of mitochondrial gene, cytochrome oxidase 1 (CO1), created a reference library of these sequences, and using a BLAST search engine in the NCBI GenBank database we assessed species and genera identity of isopods.

To date, we were able to identify seven unique stream species and four unique wetland species of isopods. We didn’t find an overlap between species which suggests presumably isolation of stream and wetland populations of isopods and may potentially provide an evidence that stream and wetland arthropod communities do not overlap as well. We are currently working on reconstruction of phylogenetic relationships between these isopod species.

10/06/19: We are currently exploring phylogenetic relationships between stream and wetland isopod species.

04/26/19: Nina presented her final poster at the ERHS Research Symposium.

02/22/19: Nina, my mentee, a high school student, who was working on this project since September 2018, presented her research project earlier this week at her school’s science fair and got 3rd prize! So exciting!

During my doctoral studies at Cincinnati, I was also involved in microsatellite motif study conducted in Dr. Theresa Culley’s lab. Microsatellites, also known as simple sequence repeats (SSR) or short tandem repeats (STR), are typically defined as repeated sequences of 1-6 bases found throughout the nuclear and plastid genomes of eukaryotes. For many researchers, microsatellites continue to be the marker of choice for surveys of genetic diversity and structure, as well as paternity analysis and mating system estimates in which codominance is essential.

In this project we explored the relationship between microsatellite motif type and detectable genetic variation in plant populations, which is critical when a researcher determines which markers are associated with higher levels of genetic variation. To guide researchers in their choice of molecular markers, we conducted a literature review based on 6,616 microsatellite markers published from 1997-2012. We examined relationships between heterozygosity (He or Ho) and allele number (A) with the following marker characteristics: repeat type, motif length, repeat frequency, and microsatellite size, as well as their variations across taxa. Our results showed no significant differences in genetic variation between imperfect and perfect repeat types, but dinucleotide motif lengths exhibited significantly higher A, He, and Ho than most other motifs. Repeat frequency was positively correlated with A, He, and Ho, but correlations with microsatellite size were minimal or non-significant. We concluded that researchers should carefully consider their choices specific to the desired application; and if researchers aim to find high genetic variation, dinucleotide motif lengths with large repeat frequencies are recommended.

I conducted this project in Dr. Ron DeBry’s lab at the beginning of my doctoral program at the University of Cincinnati. Flies of the Sarcophagidae family are known as forensically important insects; that is why studies of their identification and systematic relationships are critically important. The phylogenetic analysis which included mtDNA (COI, COII and ND4) provided good resolution for most nodes. However, the mtDNA gene tree might not be identical to the species tree, so it was necessary to obtain additional data from nuclear genes. Such new data might increase the support for the mtDNA tree or support a different phylogeny. Our results showed that adding nuclear PER gene in most cases maintained or improved support in the Bayesian Inference tree. However, we also find support for some novel relationships.

I worked on this project while I was a part-time researcher at the Institute of Cytology, RAS in St. Petersburg, Russia. I worked at the Laboratory of Cell Biology in Culture under the direction of Dr. Natalia Mikhailova. The project was on molecular phylogeny and ecological adaptations of the Cerastoderma and the Littorina snails collected in the intertidal zone of North-European region. We have recently published our paper on the evidence of hybridization between two species of littoral snails in the intertidal sites of the Barents Sea, using RAPD nuclear marker.

Dissertation. Candidate of Science: The effect of defense responses of snails on development of trematode partenitae (with a focus on the family Echinostomatidae) (Alina Avanesyan, 2002; Herzen State University, St. Petersburg, Russia; in Russian)

Advisor: Dr. Gennady Ataev, Professor, Department Chair, Department of Zoology, Herzen State University, St. Petersburg, Russia

The focus of my Candidate of Science dissertation was cellular immune response of Biomphalaria snails to infection by Echinostoma trematodes. Biomphalaria snails are freshwater pulmonate snails, native to Caribbean and South America. In my research, I used two species, B. glabrata and B. pfeifferi. Biomphalaria glabrata has been a primary model species for investigating snail defense mechanisms because it is an intermediate host for the human blood fluke, Schistosoma mansoni, a dangerous parasite that infects millions of people worldwide and causes the disease that is called schistosomiasis. For my research, I used other, less dangerous, but still wide-spread trematodes – Echinostoma caproni and E. paraensei, which are intestinal parasites of mammals and birds and which also undergo their larvae development in Biomphalaria snails. In previous studies on B. glabrata, two strains of this species have been identified: a strain which exhibits resistance to infection by E. caproni (my primary study species) and a strain which is susceptible to infection by this trematode. In my research, I was interested in exploring the role of hemocytes in snail defense mechanisms and how a hemocytic response might differ between resistant and susceptible snails.

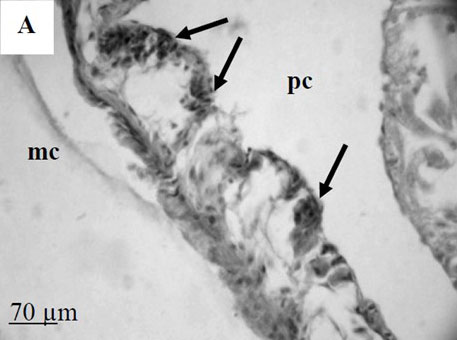

I worked under the direction of Dr. Gennady Ataev in the Laboratory of Experimental Zoology at the Department of Zoology at Herzen State University. Snail defense mechanisms to infection by trematodes was the main focus of the lab research. For my dissertation project, my primary objectives were (1) to identify and characterize the hematopoietic tissue in B. glabrata snails, (2) to compare the structure, mitotic activity of the hematopoietic tissue, as well as encapsulation of parasites by hemocytes in resistant and susceptible strains (both qualitatively and quantitatively), and (3) to perform morphological analysis of Echinostoma larvae (sporocyst) development in B. glabrata snails.

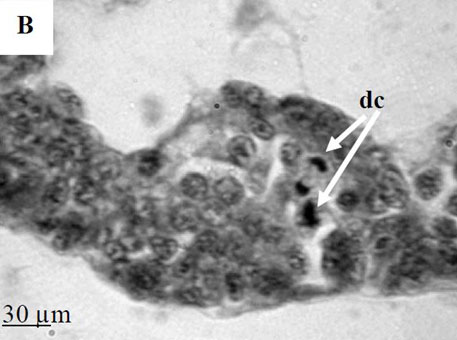

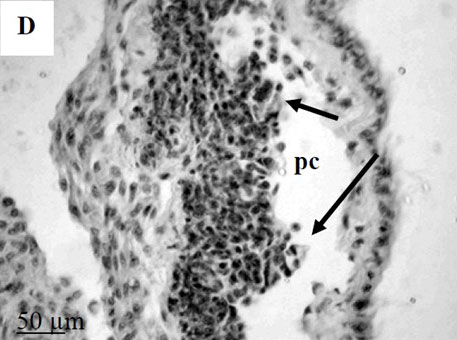

By the time I started this project, the location of the hematopoietic tissue in invertebrates, and particularly in snails, was poorly understood. We found that the hematopoietic tissue in Biomphalaria snails (so called amebocyte-producing organ, or APO) is located between the pericardium and the mantle epithelium. APO is composed of numerous cellular aggregations; they are located near the external surface of the pericardium and lacunas of the blood system. The number of cell aggregations In non-infected snails did not exceed 5; the cross-sectional area of each aggregation ranged from 25-50 µm. The aggregations varied from round, oval, and elongated to amoeboid shape, and comprised of clustered cells with the basophilic cytoplasm and oval-shaped nuclei.

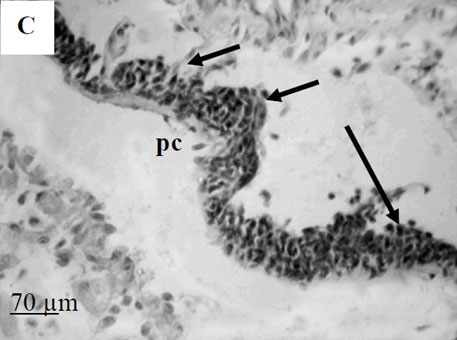

To further explore defense mechanisms B. glabrata snails, we performed a comparative histological analysis of the structure and mitotic activity of the hematopoietic tissue, as well as migration of hemocytes from the APO to the location of E. caproni sporocyst in resistant and susceptible snails. Snails were dissected in certain time intervals (from 1h to 30d post infection); tissues were then fixed and embedded in paraffin. Sections (5 µm thick) were prepared using a microtome, stained (using Erlich’s hematoxylin-eosin), and screened under the microscope. We found that there was a greater cellular immune response in resistant snails compared to that in susceptible snails – i.e. increased cell proliferation in the APO, increased migration of hemocytes to the location of the sporocyst, and successful encapsulation of the sporocyst. In susceptible snails, however, even though we also observed increased cell proliferation in the APO and aggregations of hemocytes near the sporocyst, this cellular response had never resulted in the encapsulation of the parasite, and the sporocyst continued its development and migration to the snail heart area.

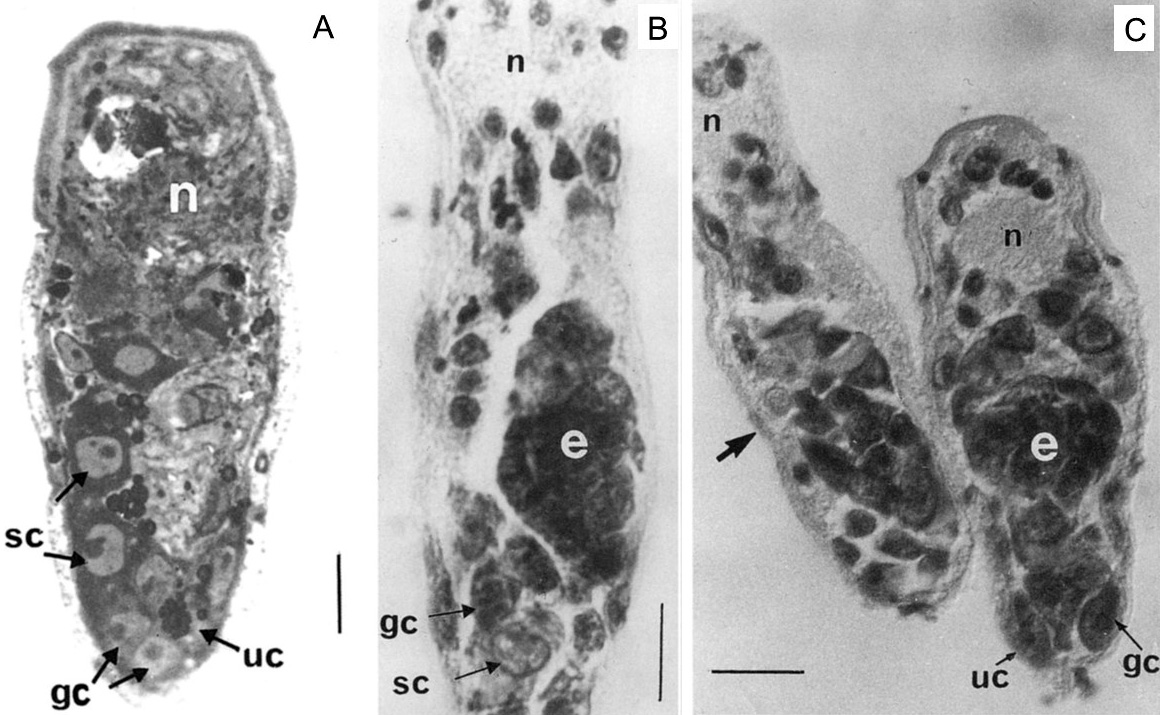

As part of my dissertation, I explored development of Echinostoma trematodes in Biomphalaria snails. I focused on the germinal elements of Echinostoma miracidia and performed comparative morphological analysis of germinal cells development in E. caproni and E. paraensei. Germinal material in Echinostoma miracidia is represented by germinal cells (primary and/or secondary) and undifferentiated cells. The germinal cells are quite large (cross-sectional area is 27.0 ± 0.8 µm2), with a large bubble-shaped nucleus and a basophilic cytoplasm. We found that miracidia of E. paraensei already contained embryos, and their sporocysts released mother rediae a few days earlier than sporocysts of E. caproni. Overall, our analysis of germinal cells development provided additional support to previous findings that species E. caproni and E. paraensei distinct species.

Ataev, G.L., Dobrovolskij, A.A., Avanessian, A.V., and E.S., Loker (2001) Germinal elements and their development in Echinostoma caproni and Echinostoma paraensei (Trematoda) miracidia. The Journal of Parasitology 87 (5): 1160-1164. file_downloadfull text

Ataev, G.L., Avanessian, A.V., Loker, E.S., and A.A. Dobrovolskij (2001) The organization of germinal material and dynamics of mother sporocyst reproduction in the genus Echinostoma (Trematoda: Echinostomatidae). Parazitologia 35 (4): 307-319.(In Russian) exit_to_applink to publication file_downloadfull text

Ataev, G.L., A.A. Dobrovolskij, A.V. Avanessian and C. Coustau (2000) Significance of amoebocyte-producing organ of Biomphalaria glabrata snails (strains selected for susceptibility/resistance) in cellular response to Echinostoma caproni mother sporocysts infection. Proceedings of the symposium on ecological parasitology at the turn of the millennium, St. Petersburg, Russia, 1-7 July, 2000. Bulletin of the Scandinavian Society for Parasitology 10 (2): 65. file_downloadfull text